How Developmental Evaluation Delivers Evidence to Support Locally Led Development

In 2021, USAID Administrator Power presented a new vision for global development that focuses on local partnerships and participation. It aims for 50 percent of the Agency’s programming “to place local communities in the lead to either co-design a project… or evaluate the impact of our programs” by 2030.[1] Because co-design – also called co-creation – involves sharing control and planning in ways that other approaches do not, those facilitating these projects will need to apply non-traditional practices of generating and using evidence.

Co-creation brings people together to find solutions using a participatory process which enhances local ownership of programs while complicating monitoring and evaluation. Typical project monitoring uses indicators to measure progress. Co-design challenges such precise measures because it involves ambiguity initially about which tasks and outputs will be used. Further, some co-created ideas may be tested and discarded for more promising solutions. Because conventional evaluation emphasizes accountability, it may misjudge such experimentation as failure rather than a part of innovation.

One non-traditional learning approach that supports co-design and has been piloted and adopted by USAID is developmental evaluation (DE). In DE, evaluators are embedded in a program team, working with them to innovate throughout implementation. Embedding alongside partners for an extended period enables DE to generate evidence as events evolve and then use it to inform decision-makers on how to manage adaptively as new realities emerge. DE works with co-creation’s dynamic process by:

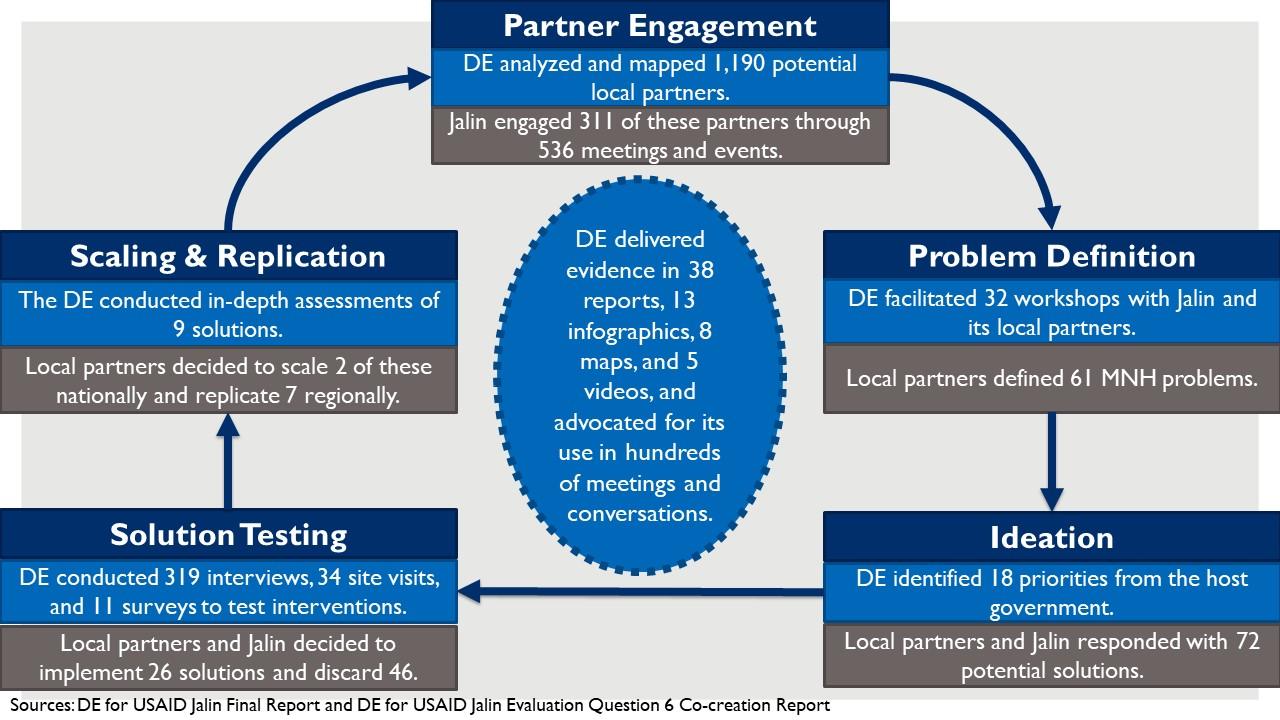

- Delivering real time, ongoing feedback. Conventional performance evaluation delivers findings at a program’s middle or end, while DE generates evidence throughout implementation. Real time feedback enables partners to learn continuously while co-creating, delivering data they need for decision-making concurrently with the process rather than at an arbitrary midpoint or end. Routine information can help program managers monitor work with local partners, which Administrator Power’s speech acknowledges is “riskier.” USAID/Indonesia’s DE supported local partners to co-create solutions to improve maternal and newborn health (MNH) by establishing a stakeholder feedback loop which won USAID’s 2021 CLA Case Competition. The figure below shows how this DE generated evidence and supported its use throughout Jalin’s co-design process, amplifying the voices of local partners and stakeholders.

- Formalizing a meaningful role for local partners and stakeholders in evaluation. Evaluations typically incorporate beneficiaries' and stakeholders’ views through interviews and focus groups. These are often anonymized and weighted equally with traditional implementers, causing local partners to struggle to see their ideas reflected in evaluations. DE, on the other hand, collects data from partners and converses with them to interpret findings and shape recommendations that have their buy-in for sustainability (see diagram below). Unsurprisingly, USAID’s DE Pilot Activity (DEPA-MERL) found that 60 percent of stakeholders preferred DE over traditional evaluation and 80 percent of stakeholders would recommend DE to other organizations

- Connecting performance improvement with systemic change. While conventional evaluation often assumes a linear logic model of inputs, outputs, and outcomes, USAID’s Local Capacity Development Policy instead prioritizes understanding the relationship “between the improved performance of local actors and development outcomes at the system level.”[2] DE supports systems change by generating evidence in real time to capture unintended outcomes and contextual changes and to allow for iterative decision-making that matches co-creation’s cadence. For example, USAID conducted a DE to study a system of 50 local organizations in Cambodia to improve their collective action to help children live in safe, family-based care.

- Being intentionally flexible in its design. Because DE is intended to work in complex systems, the approach itself and its methods can be adapted to fit different programs’ needs. Inherent flexibility is part of what makes DE suited for co-designing projects that may change over time as local partners provide input and ideas are tested and modified. USAID has conducted 14 DEs in eight sectors since 2010 which varied significantly in duration, budget, and team structures to fit the programs they evaluated. Furthermore, USAID recognizes DE as a type of performance evaluation in its Program Cycle Operational Policy specifying that it fulfills Mission and Operating Unit requirements for evaluating programs.

Figure: DE generated evidence and supported its use at each stage of USAID Jalin’s co-creation process in Indonesia (2018-2021).

Making aid inclusive necessitates changing how donors and practitioners work. This means embracing new development approaches, rather than tweaking old methods. Longstanding monitoring and evaluation practices may not prove adequate to generate the evidence to guide the change that needs to happen. DE offers an alternative that USAID has piloted successfully and adopted in its Operational Policy and is uniquely suited to supporting local partners as they take the lead.

--

[1] Power, S. “A New Vision for Global Development.” November 4, 2021. Georgetown University, Washington, DC. Keynote Address.

[2] USAID Local Capacity Development Policy DRAFT. August 2021. Version 8.